Beyond the Screen: How Games Make Us Feel the Weight of Our Choices

This cause-and-effect isn't just a mechanical necessity—it's what separates games from every other medium. Movies show you consequences; books describe them; games make you live them.

In Red Dead Redemption 2 Arthur Morgan is not well, and you can feel it in your controller.

It starts subtly with a persistent cough during routine conversations, stamina that depletes just a little faster during gunfights, a character model that gradually becomes more gaunt and weathered. For hours, maybe dozens of hours, you experience Arthur's declining health not through cutscenes or exposition, but through the fundamental mechanics of play. Your horse rides feel more labored. Your aim wavers slightly.

When the tuberculosis diagnosis finally arrives, it doesn't feel like a narrative surprise it feels like a confirmation of something your hands already knew

Beyond the Health Bar

Traditional game design teaches us that consequences should be immediately visible and mechanically clear. Lose a boss fight, restart the level. Make the wrong dialogue choice, lose reputation points. Kill an important NPC, lock yourself out of their questline. These mechanical consequences create straightforward cause-and-effect relationships that players can understand, predict, and optimize around.

But Red Dead Redemption 2's approach to Arthur's illness reveals something profound about how emotional weight actually works in interactive media. The most devastating consequences often have nothing to do with losing abilities, missing content, or failing objectives. Instead, they live in the liminal space between what happens mechanically and what happens psychologically.

Personal Investment Through Accumulated Time The Walking Dead doesn't create emotional stakes through exposition about why Clementine matters it builds them through shared experience. You care about her because you've spent hours teaching her to shoot, protecting her from walkers, and watching her adapt to increasingly dire circumstances. When consequences threaten that relationship, the emotional weight becomes unbearable not because the game tells you it should be, but because you've lived through the construction of that bond.

The UX of Heartbreak

Interface as Extension of Character State Some games push this concept even further by making interface elements reflect character condition.

Silent Hill 2's radio static creates constant anxiety that mirrors James' psychological state.

Hellblade's audio design makes players experience Senua's psychosis through directional whispers and competing internal voices.

SOMA uses interface corruption to reflect the protagonist's disintegrating sense of reality, making players question not just what's happening in the game world but whether their own perception can be trusted.

When Emotional Design Fails

The Karma Meter Problem Games like inFamous or Fable often reduce complex emotional consequences to simple numerical tracking. While these systems provide clear mechanical feedback, they can diminish emotional weight by making consequences feel gamified rather than genuine. Players optimize for meter progression rather than wrestling with moral complexity.

Consequence Overload Detroit: Become Human shows every possible consequence branch in its flowchart system, which can paradoxically reduce emotional investment. When players can see all possible outcomes mapped out like a strategy guide, choices feel less like genuine decisions and more like puzzle solutions with optimal paths to discover.

The Disconnect Problem Many games fail to bridge the gap between narrative consequence and mechanical experience. A character might deliver devastating dialogue about loss or betrayal while the gameplay remains completely unchanged, creating cognitive dissonance that undermines emotional investment.

Lessons for Emotional Consequence Design

Red Dead Redemption 2 and similar successes suggest several principles for creating consequences that feel emotionally real:

Build Relationships Before Threatening Them Consequences only matter when players care about what's at stake. Fire Emblem's permadeath system works because players develop genuine attachments to individual units through gameplay investment, not exposition. The emotional weight comes from potentially losing characters you've spent time developing and customizing.

Make Consequences Emerge from Character The most resonant consequences feel inevitable in retrospect. Arthur's illness feels emotionally consistent with the game's themes of changing times and inevitable endings. Players understand the consequence even if they wish it weren't happening.

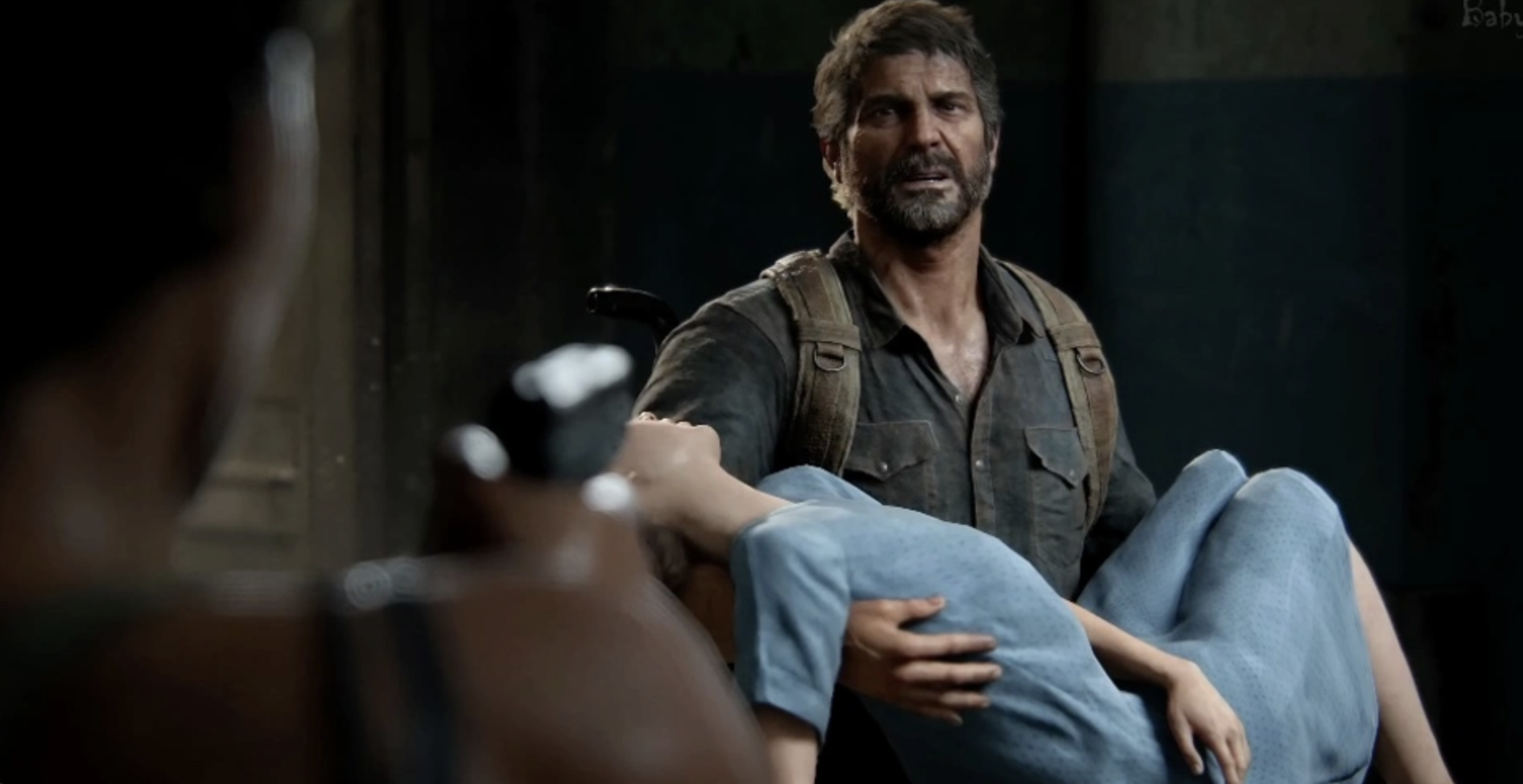

Embrace Gradual Revelation Real emotional weight often builds slowly rather than arriving in single dramatic moments. The Last of Us builds the relationship between Joel and Ellie through hundreds of small interactions before putting that relationship at the center of its climactic moral choice.

Design for Embodied Experience The most successful emotional consequences are felt through the body of play through controller feedback, through mechanical changes, through the physical act of interaction. They create memories that live in players' hands as much as their minds.

Conclusion

The most powerful consequences in gaming history weren't about losing health points or missing cutscenes. They were about forcing players to confront fundamental questions about mortality, morality, and meaning and then making them live with the weight of their answers.